Dengue is caused by Dengue virus (DENV), a mosquito-borne flavivirus. DENV is a single-stranded RNA positive-strand virus of the Flaviviridaegenus Flavivirus. This genus also includes the West Nile virus, Tick-borne Encephalitis Virus, Yellow Fever Virus, and other viruses that may cause encephalitis. DENV causes a wide range of diseases in humans, from self-limited Dengue Fever (DF) to a life-threatening syndrome called Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (DHF) or Dengue Shock Syndrome (DSS).

There are four antigenically different serotypes of the virus (although a report from 2013 suggests a fifth serotype has been found): DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4.

Here, a serotype is a group of viruses classified together based on their antigens on the virus’s surface. These four subtypes are different strains of dengue virus that have 60-80% homology between each other. The primary difference for humans lies in subtle differences in the surface proteins of the different dengue subtypes. Infection induces long-life protection against the infecting serotype, but it gives only a short-term cross-protective immunity against the other types. The first infection causes mostly minor diseases, but secondary infections have been reported to cause severe diseases (DHF or DSS) in both children and adults. This phenomenon is called Antibody-Dependent Enhancement.

Figure 1. Dengue virus particle and microscopic picture of dengue viruses.

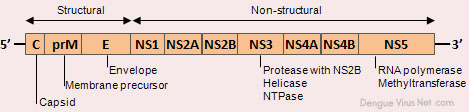

DENV is a 50-nm virus enveloped with a lipid membrane (see Figure 1). There are 180 identical copies of the envelope (E) protein attached to the surface of the viral membrane by a short transmembrane segment. The virus has a genome of about 11000 bases, which encodes a single large polyprotein cleaved into several structural and nonstructural mature peptides. The polyprotein is divided into three structural proteins, C, prM, and E; seven nonstructural proteins, NS1, NS2a, NS2b, NS3, NS4a, NS4b, and NS5; and short non-coding regions on both the 5′ and 3′ ends (see figure 2). The structural proteins are the capsid (C) protein, the envelope (E) glycoprotein, and the membrane (M) protein, itself derived by furin-mediated cleavage from a prM precursor. The E glycoprotein is responsible for virion attachment to receptors and the fusion of the virus envelope with the target cell membrane, which bears the virus-neutralization epitopes. In addition to the E glycoprotein, only one other viral protein, NS1, has been associated with a role in protective immunity. NS3 is a protease and a helicase, whereas NS5 is the RNA polymerase in charge of viral RNA replication.

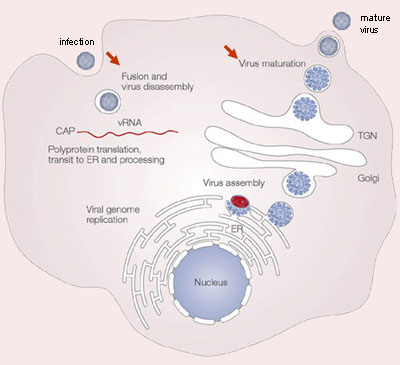

The life cycle of dengue involves endocytosis via a cell surface receptor (see video 1 and figure 3). The virus uncoats intracellularly via a specific process. In the infectious form of the virus, the envelope protein lays flat on the virus’s surfaces, forming a smooth coat with icosahedral symmetry. However, when the virus is carried into the cell and lysosomes, the acidic environment causes the protein to snap into a different shape, assembling into a trimeric spike. Several hydrophobic amino acids at the tip of this spike insert into the lysosomal membrane and cause the virus membrane to fuse with lysosomes. This releases the RNA into the cell, and infection starts.

The DENV RNA genome is in the infected cell and translated by the host ribosomes. Cellular and viral proteases subsequently cleave the resulting polyprotein at specific recognition sites. The viral nonstructural proteins use a negative-sense intermediate to replicate the positive-sense RNA genome, which then associates with capsid protein and is packaged into individual virions. Replication of all positive-stranded RNA viruses is closely related to virus-induced intracellular membrane structures. DENV also induces extensive rearrangements of intracellular membranes, called replication complex (RC). These RCs contain viral proteins, viral RNA, and host cell factors. The subsequently formed immature virions are assembled by budding of newly formed nucleocapsids into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), thereby acquiring a lipid bilayer envelope with the structural proteins prM and E. The virions mature during transport through the acidic trans-Golgi network, where the prM proteins stabilize the E proteins to prevent conformational changes. Before the release of the virions from the host cell, the maturation process is completed when prM is cleaved into a soluble pr peptide and virion-associated M by the cellular protease furin. Outside the cell, the virus particles encounter a neutral pH, which promotes dissociation of the pr peptides from the virus particles and generates mature, infectious virions. At this point, the cycle repeats itself.